This weekend I planned to take a kayak trip down the Delta River, from Tangle Lakes to just below Phelan Creek and Rainbow Ridge. But the weather forecast was bad, so at the last minute (inspired by this blog post popping up in my news feed) the plan was changed to visit the old mining town of Nabesna. Nabesna is at the end of Nabesna Road in Wrangell-St. Elias National Park, America's largest national park (larger than Vermont and New Hampshire combined), which contains only two roads: The McCarthy Road to Kennicott, where all the visitors go, and the Nabesna Road, where almost no one goes. I've been to the end of the Nabesna Road before, and walked up to the Rambler Mine, but I didn't know there was another mine and ghost town just another mile down the path.

I couldn't find much info about Nabesna online, other than it's about 2 miles past the official end of the road, so I decided to just go for it. Worst case scenario I spend a day hiking off the Nabesna Road, which isn't so bad. Drew and I left Fairbanks about 8:00pm Friday, camped out next to the Chistochina River just east of Gakona, and got up early to hit the Nabesna Road around 8:00am. We stopped at the ranger station at the beginning of the road in Slana, where we got a free CD of an audio tour to play along the road. The narration was interesting, it was worth the stop. The ranger asked where we heading and I said we wanted to try to get all the way to Nabesna. She told me what I already knew, that the road ends about 2 miles short of the town. I asked if there was any possibility of driving the final 2 miles and she said no, 'ankle express' only. I didn't press on whether she was just saying that because she didn't think we'd make it. With that, we headed down the road.

For the first half of the road, there's national park on the right side and national preserve on the left side. The main difference is that only local subsistence hunters can hunt in the park. We saw many spruce grouse on the road, and we intended to make a dinner out of a few but could only go after grouse on the left side of the road. We did get 4 grouse, and decided that was enough so just passed by the rest.

By the way, do you know the fast way to clean a spruce grouse? The Alaska Fish and Game website mentions it as an aside, with the advice that it's 'probably better demonstrated than described'. So, here's a video where I demonstrate it. This is absurd enough that I think it's more interesting than anything, but this is a video of me literally ripping a grouse in half. You've been warned:

We parked at the end of the road and decided to hike the last bit to Nabesna. ~1.5 miles further on we came to a fork in the road, with a very overgrown path ahead and an opening to smelly tailings mud on the right. We took the right fork and were at what I assume was the Nabesna processing plant (the actual mine was visible much further up the mountain).

We had left the bulk of our water supply in the car, hoping to find a stream to filter from, but none were apparent. More importantly, we realized we left the beer in the car. After walking the road in I was pretty sure my car could make it, so we left our packs, walked the short distance back to the car, and drove the car all the way in to Nabesna. No big difficulty, just an exercise in dodging ruts. A car with less ground clearance might have trouble as the entrance/exit angles ot some of the mudholes was steeper than it looks in this video. I parked at the garage next to an old yellow truck:

We walked on into town and started looking into the various cabins. Apparently this town once housed around 200 people. We found 4 rows of cabins, with possibly more hidden in the brush, and the two middle rows had boardwalks down them:

Near the center were two larger cabins which, judging by the contents, were the lab/workshop and the office/kitchen. We settled upon the office as the most welcoming, and cached our gear inside.

Time to explore!

Item number one in the 'do not touch' list. Potassium Nitrate is a strong oxidizer, and being sealed for so long, crystals may form under the lid that get crushed/scraped when opened. I'm not sure how dangerous that is without a flame nearby, but now isn't the time to find out:

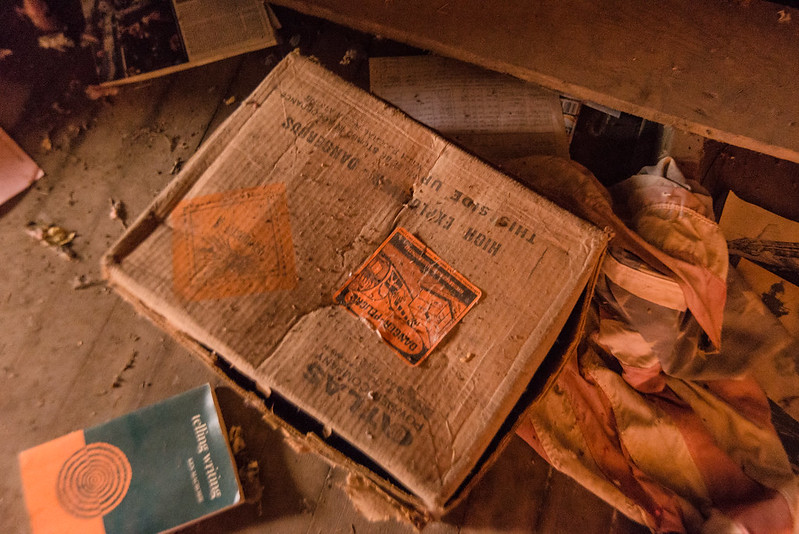

Item number two for 'Do not touch'. Not sure if this is just a box or if there's actually anything dangerous in it. Old dynamite sweats nitroglycerine, which is a contact explosive:

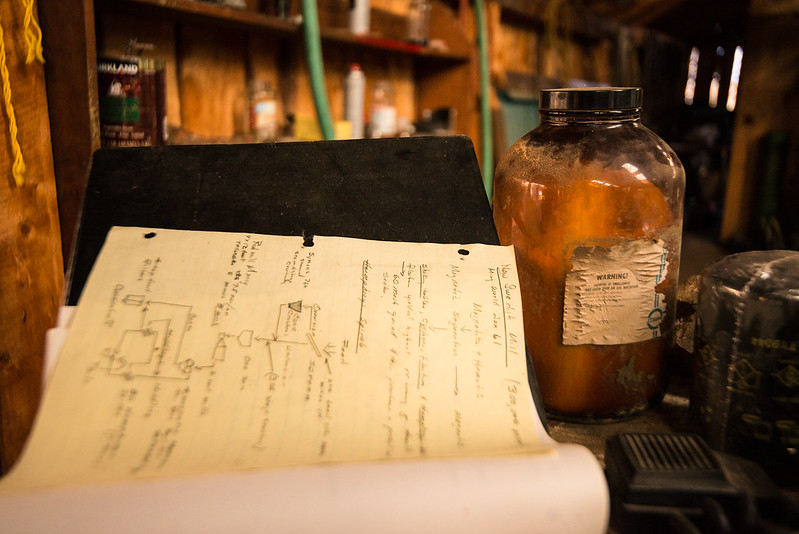

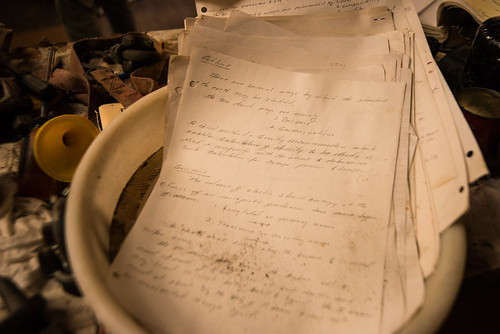

Lab notes, unmarked chemicals. We'll not touch that one too just to be safe:

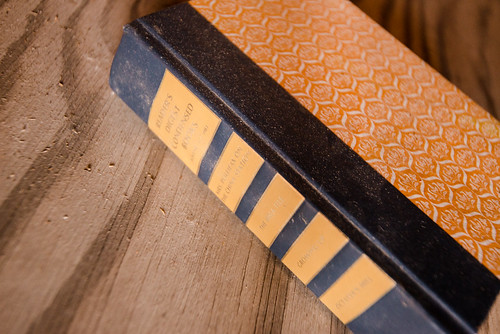

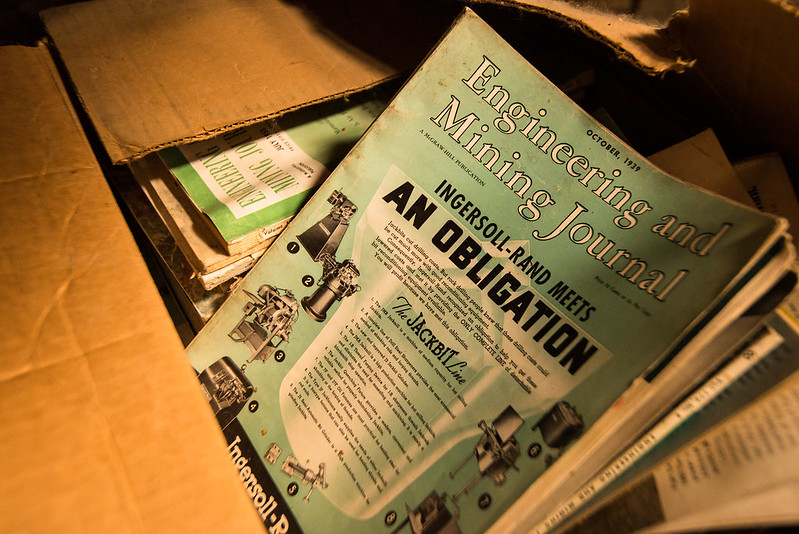

1939 mining journals. I think the mine was most active in the 30's-50's, though there was a good bit of clutter from the 80's and a couple of more recent pieces:

We then walked over to the processing plant for more exploring:

There was a chute coming from the (dry) stream uphill, leading to this big turbine:

Then flywheels set in the ceiling above it:

It looks like they tapped the stream for water power, turning the turbine for electricity and the flywheels to power some machinery directly.

The view from the plant of the mountains and river was spectacular:

By this point it was getting late, time to cook dinner. Drew found a splitting maul and an axe so we cut some wood, cleaned the grouse breasts, and built a smoker out of some scavenged metal grate, aluminum foil from the kitchen, a beat up washtub and some planks to seal it. We ate 2.5 birds for dinner and used the rest to make toasted grouse and pepperjack sandwiches for lunch the next day.

From looking like some horrific thing from your nightmares to tasty sandwiches:

The Sun was starting to go down, and we expected it to get chilly at night so we cleared an area in the middle of the office floor to set up our tents, as seen in the first picture here. And we were never heard from again...

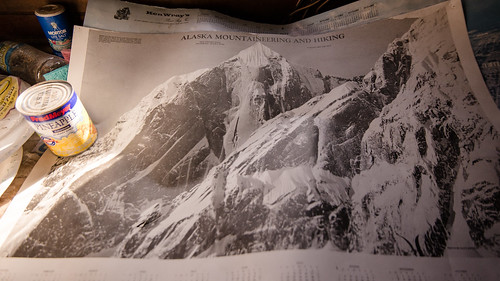

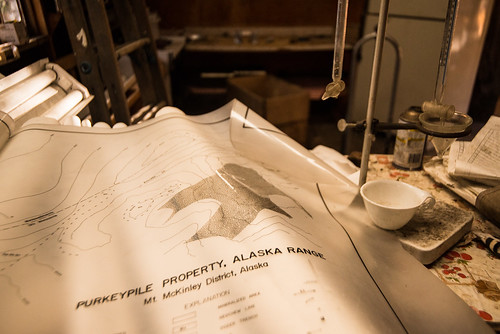

Well I can at least say it was VERY dark in my tent, in a building, under an overcast sky. But it was quiet and calm and warm(ish). I was woken up by some unidentified small animal scampering through the piles of old maps right next to my tent. We packed up and headed back to Fairbanks, with a last view of ~16,000 fot Mt Sanford on the way out:

BONUS ADVENTURE

Near Isabel Pass there's a road that looks like it goes up towards a glacier. We decided to see how far it goes. The answer is 2 miles or so, as the road gradually turns into a creek. Here's 4 minutes of video from driving back out, so the creek turns more roadlike the further you go.

Also, this: