Well hello folks. I'm writing from Longyearbyen, Svalbard:

The sign out the front door of the airport is interesting - 'You're a long way from everywhere, and try not to get eaten by a polar bear':

Longyearbyen is one of the northernmost settlements in the world, at about 78 degrees north on a remote, rocky island in the Arctic Ocean north of Norway and east of Greenland. Go ahead, look it up; it's pretty far up there. Here's a GPS track of my travel to get here:

The Sun hasn't risen since I got here, and won't for another couple of months, but the place is quite pretty regardless:

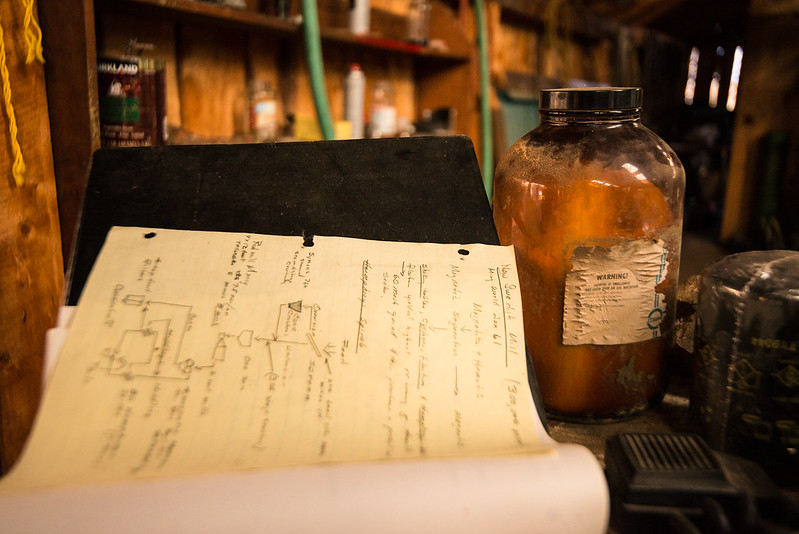

I'm here for a rocket campaign we're calling C-REX, which stands for Cusp Region EXperiment. That site has more info, but the short version is we're studying a density anomaly that occurs in the Earth's magnetic cusp (a region of the magnetosphere, near the north and south poles, open to the solar wind). We will launch a 21 meter rocket to around 600km altitude (higher than the space station!) and it will release 24 sub-payloads on the way back down. These sub-payloads are artificial chemical-clouds that will glow in the twilit sky, some of them drifting with the high altitude wind and some convecting with the magnetic field. This summer I went to North Carolina or a test launch of this system and, though that first test was unsuccessful, we did have a mostly successful launch on the second attempt. I now realize I never wrote that up here, so here is a picture and a video of the test release:

There are more polar bears (isbjørn - 'ice-bear') than people on Svalbard, and to quote a recent Facebook status of mine: "The polar bear is not only the largest land predator on Earth (and unequaled in sheer physical power), it's also the only one that will attack humans as a regular matter of finding food, rather than only attacking humans when it's sick or weak or starving or defensive. They can go 8 months without eating, and can smell a seal buried under 3 feet of snow from a mile away. It spends its whole life alone, only tolerating other bears for mating and brief interactions, and is constantly on the move, walking a few thousand miles per year. It is also an excellent swimmer, with one radio collared bear having swam continuously for 9 days through the Bering Sea to reach ice 400 miles from land, where she then immediately walked another 1,100 miles." They're amazing animals but require caution and respect, so UNIS (University Center in Svalbard) provides a training class that includes polar bear behavior and practice with flare guns and rifles. Here's me firing a flashbang out of the flare gun. Yes, we're trained to look away from the signal gun when we fire it, due to 1. It's not that accurate of a weapon to begin with, and 2. The possibility of blowback into your eyes:

I also took a couple of visits up to the KHO Observatory to help install cameras there. To get to KHO we drive up to Mine 7, a few miles from town, then since the road isn't maintained in winter we switch to this awesome tracked snow wagon to climb the last mile or so to the observatory:

We pass the Svalbard EISCAT site during the snow wagon ride:

And the other morning we took our first shakedown flight in the NASA aircraft, everything seems to be ready to go. I took this shot of some aurora to the south towards the almost-but-not-quite-sunrise:

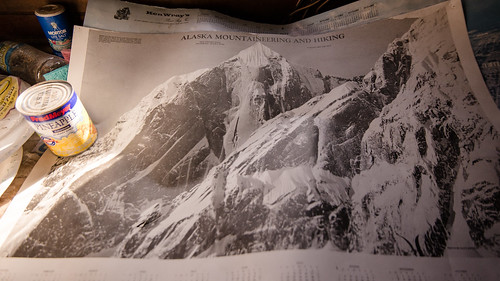

So here I am. Our first opportunity for launch comes Monday morning, my role is to fly in a NASA aircraft and photo/film the releases from the air just south of Svalbard; we also have observers running cameras at Kjell Henriksen Observatory on top of a mountain just outside Longyearbyen (central-west Svalbard) and at the Japanese Rabben Observatory in Ny-Ålesund (northwest Svalbard). I gave the local photo club a brief presentation on what to expect so hopefully some of them will be able to get some great photos of what should be a beautiful event; 24 of those glowing clouds over the epic Svalbard landscape. I know I'll have several cameras set up to hopefully get something, though that requires planning since I myself will be on the airplane at the time of launch. Here's hoping for the best.